In March, EverWalk proudly launched the 110.86 Mile Club — our virtual walking program that takes walkers on specially-curated journeys all over the world. In April, as the world moved into lockdown, I shared a journey was very close to my heart. It was the story of my mother’s childhood in Paris — and her escape from the Nazis over the Pyrenees to Portugal and then the United States.

This is an abridged version of this family story — which I had the privilege of recreating and then walking with our EverWalk Nation.

La Chemin de la Liberté (The Freedom Trail) was one of the most famous and perilous crossings during World War II undertaken by those seeking to escape Nazism. It was a journey my mother was forced to make as a teenager when the Nazis occupied Paris in 1940 and she found herself alone, the people who raised her having been taken to the death camps. She joined with a band of others, mostly Jews, many of them children, and braved their way all the way from Paris to Lisbon, Portugal, to board a boat to safety in the United States — with hopes that freedom and a new life awaited them as they sailed into New York Harbor, the Statue of Liberty’s raised torch greeting them.

My mother, Lucy Curtis, was actually born in New York City but her father died when she was two months old and her young mother didn’t want her baby and thus sent Lucy to be raised by her Uncle Atherton and Aunt Ingeborg in Paris. They lived on Rue Notre Dame des Champs in the 8th Arondissement.

Uncle Atherton was a known art collector of the 20’s and 30’s, many of his collection of artifacts now housed in the famous Louvre Museum. He and Ingeborg entertained the exciting artists of the day, Henri Matisse, Paul Gaugin, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda, to name a few.

The famous couple Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas lived in the home next door and would often tell Lucy fantastic stories. Ms. Stein encouraged my mom to write herself and Lucy as a 13-year-old won a continent-wide writing contest and was sent to England to meet the Queen and accept her award.

My mother grew up during the Great Depression, which hit Paris in 1931. After the Roaring Twenties, this was a much more somber decade.

My mother was eleven years old when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. After the Spanish Civil War, people in Europe began to pay more attention to fascist dictators Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy. But although the writing was on the wall, many people did not take Hitler seriously. It wasn’t until he invaded Poland in the fall of 1939 that the world realized the horror of what lay ahead. Immediately France declared war on Germany.

Even then, many people refused to believe that the worst could happen. . .including many of the artists and writers who were friends with my mother’s aunt and uncle. Some of these people were Jewish, and others were considered artistic “degenerates” by the Nazis. Their lives were in danger. But although some did leave for the south of France, many refused to believe what was truly at stake.

Throughout the beginning of 1940, the Germans inched closer to the Maginot Line — the armed border between France and Germany. And then the unthinkable happened. The Nazis broke through and rolled into France without a battle. And Paris fell in June 1940. Not one bomb fell, not one shot was fired.

All her life, my mother detested the sound of the German language because her first and only memories of hearing it was via loudspeakers on the Champs Elysees, the strident Haut Deutsch blaring in a tone of hatred. Many years later, the only time my mother refused to speak to me for several months was when I pursued studies of German. Like many Europeans of the World War II era, Lucy wrongly connected all German people with the Nazis, even decades after the war.

The North of France would be occupied by the Nazis while the collaborative Vichy government would enforce their rules, while the South of France remained free.

In a matter of days, everything about my mother’s life changed.

By the time the Germans arrived in Paris in the summer of 1940, two thirds of all Parisians, particularly the wealthier ones, had fled to the countryside and the south of France, in what is now known as the exode de 1940 (the exodus of 1940).

My mother with her aunt and uncle were among those fleeing Paris, not knowing if they would return, be captured by Nazis or strafed by bombers on the road. Atherton and Ingeborg had a little beachside cottage in Normandie, on the English Channel coast. This was their refuge that summer of 1940.

Once the Occupation began, many Parisians returned. My mother and her aunt and uncle did, too.

For a while, an uneasy peace settled over the city, until the beginning of 1943 — when Jews and foreigners and homosexuals and gypsies and degenerate artists and dissidents increasingly began to be arrested and deported by the Nazis into the concentration camps where most perished.

Because Atherton and Ingeborg were friends with a number of the Jews, artists and homosexuals that the Nazis sought to arrest and deport, they hid them in their garden basement.

It was a shocking day when the Nazis overtook my mother’s home on Rue Notre Dame du Champs. They pulled the well-known works of art from the walls and ate their meals directly off the canvases. And they quickly discovered the Jews Atherton and Ingeborg were hiding. Not only were the Jews sent off to camps, but my mother’s aunt and uncle were sent, too, for the “crime” they committed in protecting the Jews. From that horrific day, my mother only 17 years old, she never saw her beloved aunt and uncle again. And she learned later that they both died in the camps.

Lucy had an American passport and was set free. Alone and in shock, she was quickly welcomed into a group of about 15 neighborhood adults and children who procured an agent to help them make their way down through France, over the Pyrenees and into Portugal, where she could get a boat to the United States.

The mountain path, now known as the Chemin de la Liberte, became the path to freedom from France to Spain. The hhope, of course, in crossing the Pyrenees was to elude capture and enter Spain, crossing the country to either Portugal or Morocco and there find passage to the United States — and freedom!

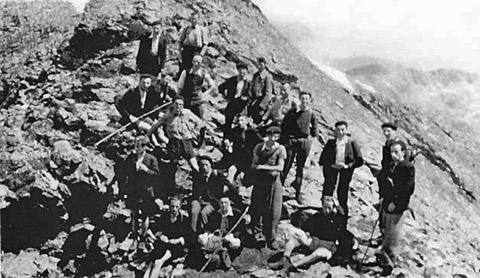

This is what my mother and her small group hoped to do! But it would not be easy. The Chemin de la Liberté was one of the most perilous mountain crossings in the Pyrenées. But to cross the Pyrenees, the expertise of the men and women whose families made their livelihoods there for generations was needed. Shepherds and chamois hunters and forestry workers and farmers all came to the aid of the refugees. Of course, there were also professional smugglers and agents who made money guiding people through the crossing.

But after November 1942, when the Germans moved into the free zone and following the Allied invasion of North Africa, Nazi surveillance increased dramatically. During the final years of the war, over 2,000 guides were executed or died later in concentration camps, and yet — over 33,000 men, women and children escaped and found their way to freedom.

Thank goodness my mother was one of them!

Crossing le Chemin de la Liberté takes four days for strong hikers with good equipment in good weather. But of course, there were old people, women, children, people in poor health and malnourished, wearing whatever shoes and clothes they had crossing in all conditions.

The trail goes over many mountain passes known as Cols, in French. The scenery is spectacular, if you are viewing on a perfect summer day. But in a raging winter storm, it can be utter hell.

The ascent only gets steeper day by day — and with limited supplies and in poor health, many feared they would not make it. The passes get higher and higher and the oxygen more limited. Without a guide, it would be easy to get lost and die. The Spanish border is only reached after an arduous climb to the 2500-meter Col de Claouère and then an equally steep descent into Spain.

Lucy was both young and fit. She had been a dancer and had dedicated several hours a day to dance classes and training. She was one of the stronger of her escape group.

My mother and her group made it across the Pyrenees and into Spain. Now they just had to get to Portugal.

After crossing the Pyrenees, the route through Spain follows one of the most famous pilgrimages in the world – the Camino de Santiago. This part of the route is known as the French Way, and it is the most popular route to the final destination of Santiago da Campostela.

As refugees like my mother crossed through Spain, they were pilgrims of the 20th century seeking religious and personal freedoms that had been destroyed by fascism.

At the beginning of World War II in 1939, the Portuguese government announced that the 550-year-old Anglo-Portuguese Alliance would remain intact. But since the British government did not seek Portuguese assistance during the war, the country (like Switzerland) was free to remain neutral.

As Hitler advanced across Europe, Portugal became the most desired escape route out of Europe. Portugal would remain neutral until 1944, when it allowed the United States to establish a military base in the Azores, and so became one of the Allied Nations.

My mother and her group had to get to Lisbon in order to get a ship to the United States.

Lisbon, in the South of Portugal, is a glorious city built in the hills over looking the Atlantic Ocean. Long a city of seafarers, this port city was a hub of activity during the war – and the long-awaited destination for my mother and her small group.

My mother and her group were able to take a steamship across the Atlantic to New York. When they arrived at Ellis Island, my mother told me how heartbreaking it was for her to see her friends taken away from her. She was an American – and not Jewish. So her re-entry into America was processed at Grand Central Station, where she slept on the floor for a few weeks.

Lucy never saw her friends again – and never found out what became of them.

My mother was hired by a wealthy family from Dobbs Ferry, who had three little girls. She became their live-in nanny, mainly to teach them French. I spoke at that school’s graduation many years later!

All my mother’s life, she was equally hurt and furious at her mother’s having abandoned her as a baby and grateful and full of love for her Uncle Atherton and her Aunt Ingeborg for making her their own daughter….and for giving her a magical childhood on Rue Notre Dame des Champs in Paris. Lucy couldn’t speak when it came to her “parents” perishing in the death camps. But she did remember the shared bravery of that little band of people with whom she shared the arduous journey of the Chemin de la Liberte.

Now the entire world finds itself again in unthinkable and extraordinary times. We are being asked to find courage and strength and resiliency that we never knew we had. Together we will face these and all the other challenges of this modern era, including Climate Change and Global Warming. And we will trust that, as happened to my mother and her Greatest Generation, we will become a bonded front of humanity because of this.

Growing up during the Great Depression and forged into resolve by the global hardships of World War II, my mother’s generation understood and expressed cooperation, compassion, hard work, a refusal to complain, and coming together for the greater good in a way our generation has never had to experience.

May we learn from them as I learned from my mother to never, ever, give up.

Onward EverWalk Nation! Let’s walk with each other through these challenges – and all that the world is giving us to be stronger, kinder, more compassionate and better human beings!

About Diana Nyad:

A prominent sports journalist, filing for National Public Radio, ABC’s Wide World of Sports, The New York Times and others, Diana has carved her place as one of our compelling storytellers and sought-after public speakers.

This is a beautiful tribute to your mother. Thank you so much for sharing it.

The creators of Curious George, M. and H. Rey took a similar journey and published a book about it.

The novel “The Nightingale” by Kristin Hannah is about the same journey.

What an amazing role model for us all to learn from, to help keep our lives in perspective. Thank you for sharing your mother’s journey.